Working on the Front Line during the pandemic

Working on the Front Line during the pandemic

Is this a temporary change or a permanent shift in the way we work?

In early February I got a mini-job offer working in an organic supermarket in Berlin. My landlord, who owned the shop, reached out to me and asked if I was available to work for a two-week period as a cashier. It was funny, I had just left my previous job in a clothing store less than a week before, and it felt like this was a saving grace. How could I be so lucky, despite working on the front line?

After the two weeks were over, I was asked if a permanent position would be of interest. I was thrilled and accepted, albeit with a slight complication: I was working an evening or two in a pub as well and wanted to be able to continue. Eventually it got sorted and a 20 hour a week, part time contract was signed. It was all going swimmingly.

The roster is in the back office of the shop and it is beautifully colour coordinated. I can spot my name easily and note which days I am working. As human beings we like order and routine. We thrive on the capacity to plan and we always try to predict. But nobody could have seen this coming.

As I began to settle into my new role (a very glamourous one, selling organic fruit and vegetable to the upper classes in the prestigious district of Charlottenburg) an unsettling feeling crept up on Berlin. By the end of the first week of my new contract, it was announced that all employees in non-essential businesses were to work from home and all bars and restaurants were to be shut.

The Corona pandemic has affected workers in all sectors. It has been an inescapable nightmare for some and a mild inconvenience for others. It is hard to imagine the impact that this will have on us in the long run. Is the change in our working lives due to Corona only a temporary measure, or will we ever be able to return to the normal way?

How has it changed?

On the Monday of the first week of lock down my mum called me and asked me what I wanted to do: remain in Germany or fly back to Ireland to spend the time with my family. I was slightly shocked. I thought about it briefly and told her I was happy to stay. I was still working a few shifts here and there in the supermarket and with that money I would be able to cover my rent.

Almost immediately after getting off the phone to her, I received a call from my boss asking if I could work that day and whether I would be able to take on more shifts over the coming weeks as some other staff were calling in sick or had no choice but to stay home and look after their children. Since the pub I worked at was closed under the new measures, I confirmed that I was able to work full time for the foreseeable future.

The change in consumer habits was noted almost immediately as the threat of a lockdown loomed. The German verb to stock up is ‘hamstern’ (literally to hamster) meaning to accumulate like a hamster. Toilet paper, tins of tomatoes and noodles; this was a global phenomenon. Trolley loads upon trolley loads arrived at the till and my arms ached by the end of the days. The panic buying was the first change.

Then came the protective measures. Gloves initially. I didn’t mind wearing them, but it was difficult to type and pick up change. My hands were wrinkled and dry at the end of my shift. Still, it was manageable. The biggest shock came at the start of the second week. Plastic sheeting draped from the ceiling at the cash points to prevent the spread of germs between customers and cashiers. It was shocking. Someone pointed out that it looked like a hospital and another like a festival tarp. I suppose that summarises the mindset of the people in this time. The sheet was completely opaque, and I could hardly see a thing. As a joke my co-workers would shout and ask if I was still there and I would reply: ‘ja, unfortunately.’ Eventually a Perspex screening was introduced so I could see who I was dealing with and what was going on again. And, just like that, it became normal.

The reason, I believe, that this situation is so astonishing to us is because we have never faced anything like it before. Speaking to a friend of mine who is working from home, he pointed out that the first week of home office was exciting because it was novel. It felt like a holiday. He found it easy to plan out and structure initially. Then, before long, came two realisations: the reality that this wasn’t going to be a two-week lock down as planned, and the monotony of the tasks he was doing daily. Without interaction with colleagues, the most enjoyable aspect of the office atmosphere is lost. Zoom calls replacing casual conversations in the kitchen and sharing beers via video chat instead of in a true, social setting doesn’t allow for the same sort of social interaction and bonding that we as humans crave. Participation in sports clubs is valued on a C.V. because it shows ability to work in a team, which is vital in almost every working environment. Human contact is something that will be almost impossible to replicate with technology and it is becoming evident from this period of social distancing. Not just in our professional lives but personal ones too.

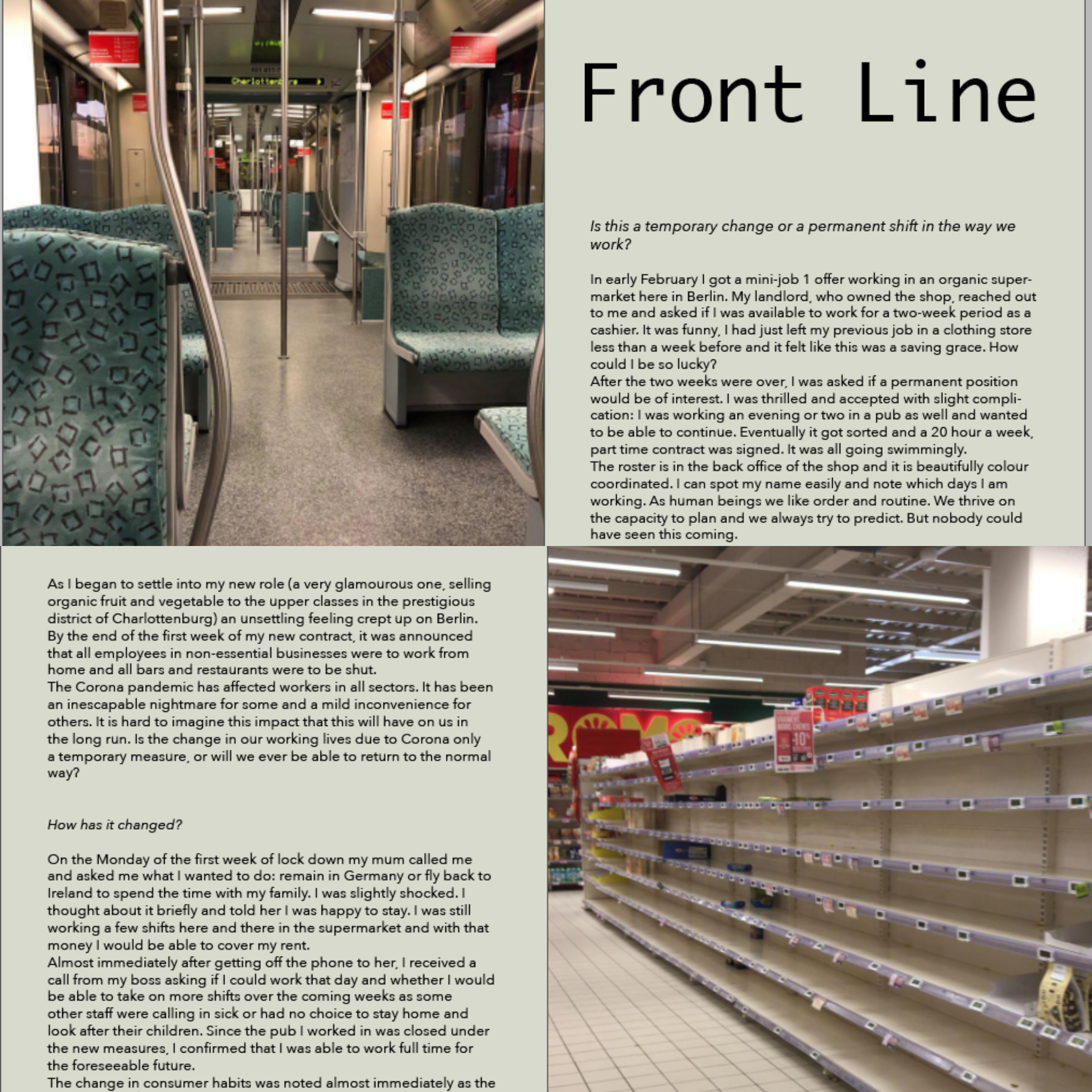

To continue to work outside of the home during a global pandemic is a strange thing. I would get the S-Bahn at peak commute times and have a whole 4-seater compartment to myself. I would be questioned by my inquisitive flatmates when I returned, asking me what it was like outside and were there many people. I would tell them the truth: I noted fewer people on the streets, but in the supermarket, it was almost as if nothing had changed. It was a microcosm exempt from the rules of normality. Although stressful at times, I am happy to be able to continue to deal with customers. Speaking with a friend who is working from home, he said the hardest part of not working in the office is the lack of casual conversations with his co-workers.

How will it impact the future of working?

It’s impossible to imagine what the outcome of this will be. Without a vaccination, it is hard to know when this process of social distancing will be over, and we can go back to normal. And I question further – will things ever be able to go back to ‘normal’?

Inevitably there will be global economic consequences to this pandemic. It’s impossible to predict exactly what they will be, but a universal recession is highly likely. Stock markets are falling, and unemployment is rising. The first I have little understanding of. The second, however, is something I have seen affect so many of my friends and family. Fortunately, most can benefit from state support, but the future is fearful and bleak. We cannot picture how our world will look in 6 months. But we can always hope.

A personal hope of mine is that low skilled workers and health care professionals will continue to be respected in the same way as they are now. Before, I found myself saying that I was just working in a supermarket or only working as a check out girl, when people inquired about my profession. Admittedly, it wasn’t the job I had envisioned myself doing after obtaining my Bachelors degree, but the truth is I thoroughly enjoy it and don’t know what else I want to do right now. I work hard so what’s the harm in working in a job that’s deemed as unskilled? Also, I would like to say you’re welcome to Angela Merkel, who seemed to value all those working on the front line, and thanked all supermarket workers for their help during this time; It’s my pleasure, Mutti.

And, of course, the biggest thanks go to those who are actually saving lives. Those in hospitals, fighting this war with science and compassion, with bravery and intellect, with physical and mental strength. They deserve all the recognition and support they receive. It wasn’t until this pandemic that student nurses in the Republic of Ireland were paid for their work. Disgraceful that it took a crisis of this magnitude for their sacrifices to be rewarded, but hopefully that’s a permanent measure now. It will forever be incomprehensible to those who do not witness what they endure, to understand the extent of their sacrifices for our benefit. Staying at home isn’t a luxury, it is a necessity. Not only to protect us, but those who are the most vulnerable and those who are the most valuable.

The only time the severity of the situation really strikes me is when I am travelling through Alexanderplatz, one of the busiest places in Berlin. To see it completely empty stirs an eerie, unsettling feeling. Then, suddenly, a bright orange jacket on a bicycle will cut through the deserted plaza. These are the delivery men and women feeding the city in lockdown. I salute them. In the mornings I see construction sites on the outskirts of the square with people working day in and day out. They wear the same colour orange, head to toe. It’s the same colour orange as the rubbish bins dotted along the streets of Berlin. These streets are still being swept. The train stations are still being cleaned and monitored. The trains are still running, and not by magic. These are only some of the few jobs that I see on my 30-minute commute. All these people deserve respect for making our communities liveable and safe, whether there is a health crisis or not. Let us continue to value them when all this madness passes.

‘Working on the front line’ is an article by Lauren Dempsey as part of our 2020 non-profit Corona-virus magazine project. You can read the whole magazine here:

Interested in joining one of our writing projects in Berlin? Please get in touch for all the details!